Herschel Dwellingham, whose drumming provided the funky underpinnings for Weather Report’s third album, Sweetnighter, passed away on April 16. He was 77 years old.

I got to know Herschel while researching my book Elegant People: A History of the Band Weather Report. I interviewed him twice, and over the years we talked by telephone many times, usually initiated by Herschel calling me out of the blue. It was always fun hearing from him. One time he called to tell me about a new project he was working on. He called the band the Sweetnighters, an obvious nod to Weather Report’s album. When Herschel needed a write-up for it, I was happy to do it for him.

Herschel had a long and varied career with an extensive list of credits not just for his drumming, but for songwriting, arranging, and producing as well. In fact, producing his own songs was his true passion. He got his first songwriting credit when he was sixteen years old and continued writing and producing to the end of his life. Many of his songs found an afterlife in television shows and motion pictures (e.g., “(Gonna Ride This) Whirlwind” as performed by the Escorts, which appeared in the 2020 film Don’t Look Up starring Leonardo DiCaprio).Herschel got his start as a musician when he was just a toddler. As he told it, “My mother told me that to keep me from crying, she used to give me two wooden spoons and a pot for me to beat on just to keep me busy so she could cook.” A little later, his parents, who were school teachers, took him to a high school prom they were working at. In the band was Earl Palmer, a drummer who has been credited with helping to invent rock and roll, and who later gained fame as a member of the Wrecking Crew, a loose collection of studio musicians who played on hundreds of top 40 hits in the 1960s and 1970s.

As Herschel remembered, “Earl Palmer was playing with the Rhythm Aces [a popular band based in Herschel’s hometown of Bogalusa, Louisiana] and I watched Earl all night, standing near the stage, just watching him. When the night was over he handed me a pair of drum sticks and that started me off. To this day, I keep four or five pairs of new sticks in my bag and I given them to kids who come up to me asking about the drums.”

In addition to the drums, Hershel learned the piano and played organ in his church. His high school bandleader taught Herschel how to write and arrange music, and he began arranging for the marching band. “I did that to keep from marching,” Herschel said. “I made a deal that I would orchestrate and arrange the half time shows to keep from marching because I hated it.” Herschel also took over the drum chair in the Rhythm Aces and starting writing his own songs. At the age of sixteen he took thirty songs he had written to Joe Ruffino, who ran two New Orleans–based labels, Ric Records and Ron Records (named after his sons). A month later, Herschel heard one of his songs on the radio, “Come On and Tell Her,” sung by Benny Freeman. All told, Ruffino released ten of Dwellingham’s songs as singles.Upon graduating from high school, Herschel moved to Boston to attend the Berklee School of Music. At Berklee, he came under the tutelage of legendary drummer and teacher Alan Dawson. Years later, Herschel said his drumming style was a combination of his Louisiana roots and the rudiments that Dawson taught. He and Dawson would often trade licks in a Berklee practice room, and Herschel would pick up gigs substituting for Dawson at local jazz gigs. He was also part of a band that included guitarist John Abercrombie, Mark Levine on trombone, and Carl Schroeder on piano. They played a mixture of dance jazz, R&B, and funk.

While Herschel was studying with Dawson, the Sugar Shack opened in downtown Boston. It quickly became Boston’s one and only place to hear the top R&B, soul and funk acts of the day. After completing his studies at Berklee, Dwellingham took over the house band at the Sugar Shack, leading a 13-piece orchestra and backing many of the name acts that came through, including Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, and Smokey Robinson, just to name a few. Herschel also did sessions for local R&B acts. There’s no question he was an important part of Boston’s Black music scene in the late-sixties and early-seventies. According to Herschel, he became known as “Boston’s Number One Soul Man.”Meanwhile, his real goal was to write and produce his own songs with the goal of achieving a national hit that could put him over the top. He did his own arranging, hired the musicians, and foot the bill for his own sessions, then either shopped the tapes to the record companies or put them out himself on My Record, a label he and his wife Alva started with Skippy White, a Boston disc jockey who also owned several record stores in the area. The first 45 he released on My Record was “Young Girl,” featuring vocalist Frank Lynch, who came under Dwellingham’s mentorship and sang in his band. Tragically, Lynch’s life was cut short when he was shot and killed by a police officer. That story was remembered in a recent Boston magazine piece which you can read here.

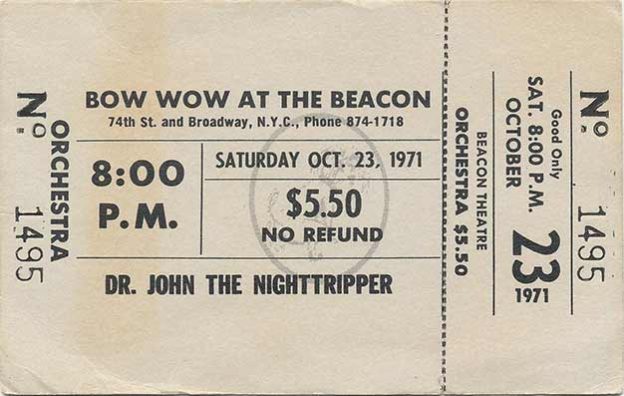

In 1971 Herschel took a song to Black Rock, CBS’s corporate headquarters in Manhattan. There he met Bob Devere, who was on Columbia Record’s Artists & Repertoire staff as manager of independent projects. In this role, Devere purchased the masters of regional hits that he thought could go national, which Columbia then put out on a subsidiary label, Date Records.

As Herschel remembered it, Devere didn’t really want to give him any time. “He said he didn’t have time to hear it. I said, ‘Well, take it in back, listen to it, and come back. We don’t have to go in.’” So Devere took Herschel’s tape back to his office while Dwellingham and his wife Alva waited in the lobby. When Devere returned, it was with a different attitude. He offered Herschel $15,000 for the master tapes, the only catch being that he wanted to re-record the vocal part using O.C. Smith, who a few years earlier had had a gold record with “Little Green Apples.” But Herschel wasn’t interested in giving the song to another vocalist and he wound up selling it to RCA instead.

A year and a half later, Devere was managing Weather Report and Joe Zawinul tasked him with finding a funky drummer for their upcoming recording session, and he thought of some R&B 45s that had come through his distributorship with the name “H. Dwellingham” on the center label. By then, Devere had forgotten all about Dwellingham’s visit, and even his name. After checking around for “H. Dwellingham,” he found Herschel in Boston and asked about the drummer on those tracks. Surprised to learn that Herschel played the drums in addition to writing the songs, Devere invited him to the Sweetnighter session. My book goes into great detail regarding the making of the album, so I won’t repeat it here. However, one thing I didn’t include in the book was Herschel’s reaction to Joe’s claim that he spent hours teaching the drummers the beat to “Boogie Woogie Waltz” and “125h Street Congress.”

“He’s full of shit,” Herschel said, laughing. “Everybody who knows me knows I was playing those beats even in my Boston days. It’s like a New Orleans drum style mixed with Alan Dawson’s jazz sensibility. If you hear the records I played on in Boston before Zawinul, you’d hear the same thing. Those beats are a combination of my Louisiana roots and George Stone’s Stick Control book as Alan Dawson taught it. I started incorporating his teaching in my playing way before Zawinul was ever in sight. That’s where that came from. Joe Zawinul didn’t teach none of us anything, especially me. I didn’t play the song more than two or three times, anyway. There wasn’t a live rehearsal—everything was done in the studio. So I don’t know what he’s talking about.”

With Eric Gravatt also in the studio for the Sweetnighter sessions, there’s been some confusion as to who played drums on what. According to Herschel, he was the sole drummer on “Boogie Woogie Waltz” and “125th Street Congress,” and he and Gravatt both played on “Manolete” (“Eric’s on the beginning of that with me”) and “Non-Stop Home.” “Non-Stop Home” was his favorite. “I liked that round jazz groove,” he told me. “That’s my ringtone for my phone. That’s what I use for my alarm.” (laughs)

“And then Zawinul wanted the tempo to speed up and that was a good finish—faster and faster and faster, intentionally.” As a session player, this wasn’t what you would normally do. “No, it wasn’t,” Hershel agreed. “I’ll tell you, bass players or keyboard players that push the tempo, I don’t play with them anymore. I don’t get high. I don’t smoke, I don’t drink. I don’t do none of that because I don’t want to mess with my built-in metronome. That’s what made me a great session player. I’ve never done anything with a click track unless it was a movie score I was playing. But all the records I played never had a click track.”

Shortly after the Sweetnighter sessions in February 1973, Herschel moved to New York City where he became an in-demand session drummer working with the likes of REO Speedwagon and Peter Nero. He also worked in the Broadway pit bands of many high-profile musicals. Aside from Sweetnighter, his best-known session work is probably Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s In the Cradle,” a gig he got from Paul Leka, who co-owned Connecticut Recording Studio where Sweetnighter was recorded several months earlier. After spending a couple of decades in New York, Herschel returned to Bogalosa where he set up his own recording studio and production company.

Through it all, Sweetnighter seems to be the thing Herschel is best known for, and people mentioned it to him for years to come. “That one little album must have put me on the map,” he told me. “Even in Europe. I was in Frankfort and I did master classes and private teaching—it was just unbelievable. My wife and my friends say I really don’t realize what I did and how important to drumming my playing was. I’m just a country boy who doesn’t think nothing about that. To me, I was just trying to make money to feed a wife and three little kids. That’s what I was doing. I didn’t think I was making history or fame or anything. Just trying to keep money in the house.”

At one point, Herschel was in New York and noticed that Zawinul was there, too. “He was in town at the Blue Note and I was playing the same night he was playing, so I couldn’t get there. So I called the club and asked for Zawinul. They said he’s on stage; call back in ten minutes. I called back and said, ‘Tell Joe Zawinul that Herschel Dwellingham is on the phone.’ I thought, this guy isn’t going to remember who the hell I am, but he came to the phone and said, ‘The Boogie Woogie Waltz man!’ I said, ‘You remember me?’ He said, ‘Man, are you kidding?! There wouldn’t be no Weather Report if it wasn’t for you.’ That’s what he called me, ‘The Boogie Woogie Waltz Man.'”

I will miss Herschel. He was a good man. Rest in peace.