Pianist Barry Harris died last week at the age of 91. According to his business partner Howard Rees, Harris’s death was caused by complications of Covid-19.

A “steadfast champion of bebop,” as the obituary in the Detroit Free Press put it, Harris was perhaps the best living exponent of the bebop style of jazz piano, revered by many for his playing and his generous spirit when it came to codifying the bebop language and teaching it to others.

Though he was never affiliated with a major educational institution, Harris was renowned for leading informal sessions in which he taught bebop to other musicians, starting in his home in 1950s Detroit, and later at various venues throughout New York City. Many significant musicians came under his tutelage, but Harris was welcoming to students at all levels. Eventually he taught clinics around the world. Harris maintained informal weekly sessions with students until just before his death. According to Mark Stryker, who wrote Harris’s obituary for NPR, Harris taught his last class, via Zoom, on Nov. 20.

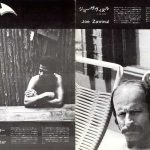

Decades earlier, Joe Zawinul was one of the recipients of Harris’s generosity. When Joe settled in New York City in 1959, the city was full of excellent jazz pianists, none of whom, according to Zawinul, sounded like the other. Joe practiced with many of them, trying to soak up as much knowledge as he could. One style that he wasn’t exposed to in Austria was bebop, and there was no one better to practice bebop with than Barry Harris, who had preceded Joe in Cannonball Adderley’s band. They used to get together at a rehearsal room at Riverside Records, which was Harris’s label.

“Barry and I used to rehearse together a lot at that time,” Joe recalled in 1984. “It was kind of a one-sided relationship in one respect, though. I got a lot from him. Coming to jazz when and where I did, I missed the bebop thing, and that was the style of piano playing I wanted to learn. To my mind, Barry was about the closest there was to the pure bebop style—after Bud Powell, that is. Barry has got that down beautifully; he’s a superb musician. We used to spend all our time at Riverside Records’s studios, rehearsing. As I say, he gave me a great deal, and I will never forget it or be able to replay him for it.”

Around 1965, Harris was involved in an incident that motivated Joe to evolve his own personal style of playing. He related the story to me in a 2003 interview:

I was standing on the corner of 52nd Street and Broadway, which is right where Birdland was. And Barry Harris comes out of a cab, and says, “Joe! I gotta tell you something, man. It’s killing me, man!”

“Yeah, what is that?”

“The tune I just heard on the radio in the cab, it was Cannonball, and I swear to God I thought it was me playing, and then they announced it was you, man. Congratulations!”

I said, “Thank you, Barry.” And I was flattered for a minute. But when I thought about it, I said, well, now… What the hell does that mean, man? He’s already copying Bud Powell, and I’m copying him. What the hell is this? So I went home… I went home, right then and there, and put all my records in cellophane, and they are still in it, stashed away. And I never listen to music. I don’t listen to music, not even to my own. I listen to music now because I have to work on it. The moment it’s done, I don’t even know the name of the tunes. I really don’t.

Joe retained warm feelings for Harris throughout his life. But as the 1970s unfolded, Harris grew disillusioned with the music scene in general, which he expressed in a 1977 Down Beat profile. “Harris doesn’t go out to listen to other musicians very often,” the article stated, “explaining that ‘the music has no class now at all.’ ‘I don’t go to clubs much, ’cause musically I can’t deal too much with most of what’s going on—the commercialism, the avant garde musicians.’”

“I’ve been able to make it here (New York) a little bit, not much,” Harris added. “I make enough to send my family some money sometimes. The last few years I’ve been much luckier than I’ve been in my life, and I’ve still never made any money in my life. I’ve made a lot of records and I’ve never received a royalty check off a record in my life. And yet, everywhere in the world I’ve been, I’ve seen my records. It’s pretty weird . . .”

Like a lot of his contemporaries, Harris felt that the younger generations of jazz musicians had sold out the music. He made those feelings clear when he was part of a 1990 jazz piano roundtable that appeared in Keyboard magazine. “Right now, the word ‘jazz’ is like a garbage dump,” he said. “Everything that they can’t classify, they say—ploop!—‘Jazz.’”

When the other panelists brought up the subject of Weather Report in the context of defining jazz, Harris went off: “What kills me about those kinds of groups is that when someone has a jazz festival, they bring these cats together and call them a jazz group. See, I’m one of those people who believes that you cannot lie twenty-three hours of the day and be real for one hour. You can’t be untruthful to something, and then suddenly be this real person and show me that you can do it.”

The interview session went on:

Richie Beirach: Barry, the thing about Weather Report is that there’s no doubt about their jazz credentials. I loved that group; they did great music. But the emphasis was not on improvisation. It was on color, orchestration, and composition.

Harris: Zawinul and all those cats wrote certain tunes that showed their intent. I mean, if you wrote those tunes under the auspices of them being jazz tunes, then you knew they were leading somewhere funny. Joe Zawinul—oh, man, I hate to talk about that cat. It’s almost like we should be blessed because he brought his music to us from Europe.

Beirach: I saw him playing with Dinah Washington, though.

Harris: I know, but when I used to be over here on 46th Street, and I’d go to the studio and practice all day, Joe Zawinul was the first person to come in and stay with me all day [i.e., learning from Harris]. So when you mention those names, I’m real negative about them. I can’t call them jazz musicians.

Kirk Nurock: What you’re saying is fascinating, because it illustrates that this gray area is very controversial.

Harris: Oh, yeah. What makes me mad is that the musicians who were working, young cats—Herbie Hancock, all these cats—they were the ones who was working! They was working more than me! They were the ones who were really helping jazz! And they are the ones who went over to somewhere else. Now, that I don’t understand. They were making it with the music—they were making it!

Beirach: Well, they were making it in your eyes, but maybe it wasn’t enough for them.

Harris: Money, you mean.

Beirach: Well, money, exposure…

Harris: Money!

. . .

Harris: See, I get funny when you mention things like Weather Report.

Nurock: I noticed.

When the journalist Leonard Feather brought Harris’s comments to Joe’s attention later that year, Zawinul laughed it off. “I like Barry Harris,” he responded. “I have no problem with what people say. He is one of the finest, but he’s a copy of Bud Powell. I have arrived, you see. Last summer the Montmartre in Copenhagen they had a list of coming attractions. They had Betty Carter, and they identified her as a jazz vocalist. They bill some band and described it as a rock group. But with my name they had no description. They just said ‘Zawinul.’ Not jazz, not rock, just me. I am my own category.”

Of course, the beauty of it all is that the world is large enough to accommodate both Zawinul and Harris. The former learned bebop so that he could leave it behind in order to forge his own style, while the latter devoted his life to spreading the bebop gospel so that it continues to be played by new generations of jazz pianists.

Rest in peace, Barry Harris.