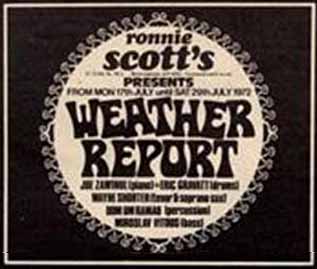

The advertisements for the show listed Eric Gravatt as the drummer, even though Gravatt had left the band in June. Taking his place was Greg Errico, whose first gig I wrote about here. By October, Errico was preparing to leave the band, so Joe and Wayne began looking for a replacement.

Ishmael, who was born and raised in Philadelphia, was then in a local band that featured original material in a funky-jazz vibe with a female vocalist. Weather Report came to town on October 14. This was the night Joe and Wayne heard Alphonso Johnson play bass with Chuck Mangione, leading to Alphonso joining Weather Report. It was also the night that Wilburn got on Joe and Wayne’s radar.

“We had a guy who sort of managed our group, and I think he was somehow connected to Wayne Shorter,” Ishmael recalled. “He went down to the show to see them—I didn’t go to the show—and he let them hear a demo tape of some originals we were working on, and they liked the drumming. Joe liked my foot. That’s what I remember the guy saying when he came back. He said, ‘Hey man, those guys want to talk to you. They want you to do an album with them. Joe really likes your foot.’ I said, ‘Wow, my foot!'” [laughs]

I asked Ishmael what Joe meant by his “foot.” “My kick drum,” he explained. “How I play my kick drum. Where I drop and how I played my kick drum. He really liked the feel of how I played.” Going back to the recording of Sweetnighter, Joe was keen on finding a drummer with a powerful bass drum sound. Ishmael fit the bill.

I have to imagine that getting an offer to play with Weather Report, let alone record an album with them, was probably the last thing on Wilburn’s mind at the time. He was twenty years old and his experience was mainly limited to local groups. “I had done some things with local bands in Jersey, New York—small club stuff, maybe a big venue where we weren’t the main draw—you know, a doo-wop group or something like that. I had backed up a lot of doo-wop groups up to that point. That was the thing in Philly.”Nor was Wilburn all that familiar with Weather Report’s music. “I had never really heard of Weather Report. [laughs] I was more into Cold Blood, Earth, Wind & Fire, Rare Earth, Chicago—that kind of stuff. I was coming from a gospel background.” Nevertheless, when the offer came, Ish was willing to give it a try.

Joe and Wayne wasted little time getting Wilburn to a gig. Ten days after they were in Philadelphia, Weather Report had a show in Washington, D.C., and they invited Wilburn to come down. “Somehow or another I was supposed to go meet them,” Wilburn told me. “They paid for me to go to D.C.; they were supposed to play at Constitution Hall. I took the Amtrak down and I think I was going to sit in or do something at soundcheck so they could get a feel for me. But something happened. They didn’t get into town and I was delayed, and it was getting late. I think the show was pushed back or something. Anyway, I didn’t meet them. So I came back to Philly and started doing my daily thing.

“And then I got a call from their manager, and he said, ‘Listen, they want you to play a gig with them.’ I said, ‘What? I have never even played with them. I have never met them. You’ve got to be kidding me.’ So I said okay.” Wilburn caught a plane to Dayton—he had never been on an airplane before—where he met the band for the first time. After checking into the hotel, he went to the Palace Theatre for soundcheck.

“I was actually playing on Greg Errico’s drums. He had these Ludwig clear acrylic drums—huge drums—and I’m not very good at playing other people’s drums. I hate that. I don’t like going and sitting in. But anyway, we did a soundcheck for about forty minutes, and I was nervous as hell.

“Then we did the concert. I had never played a room that size. Scared as hell. That was really something. It was a standing ovation. I really hadn’t understood how big they were in the jazz market. And afterwards Joe told me how great it was. Joe Zawinul was a character. Oh my God, man! He took a tape off the soundboard and gave me a cassette of it and said, ‘This is you. Listen to this. This is you!’ I didn’t even recognize me playing the drums with them. I said, ‘No, this is not me.’ He said, ‘Yeah, that’s you!'”

As I wrote in my book, so began a whirlwind that found Ishmael playing with one of the leading jazz bands of the day. A month later he was at Devonshire Sound Studio recording Weather Report’s fourth album, Mysterious Traveller. There’s no question that Wilburn’s playing was instrumental in creating the unique sound of that album, one of Weather Report’s best.

“Great memories for me out there,” Ishmael said of his time in Los Angeles. “We were out there recording, and I was staying in this little hotel bungalow. I had my own room. Dom Um [Romão] was like a mentor to me. I remember him cooking me lentil soup, stuff like that. I drove around L.A. a little bit, but I was twenty years years old. I got home sick. They flew me home for Christmas. It was weird being in L.A. with Christmas trees and Santa in shorts. I just couldn’t handle that.” [laughs]

There’s lots more about Ishmael’s experience with Weather Report and the recording of Mysterious Traveller in my book Elegant People: A History of the Band Weather Report. When I interviewed Ish for the book, I told him that Mysterious Traveller was one of my favorite albums, and that it must be gratifying to know that people are still listening to it decades later.

“It is,” he replied. “That’s my claim to fame. Every musician wants to be associated with an album like that.”