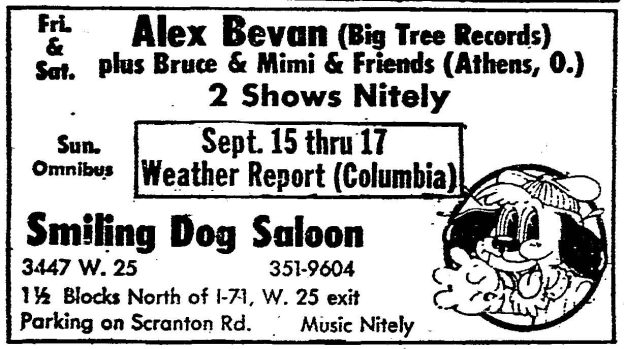

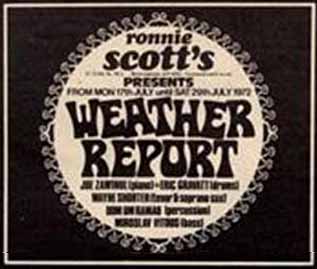

On September 15, 1972, Weather Report made its way to Cleveland, Ohio, for the first of three nights at the Smiling Dog Saloon. The band was in the midst of a four-month stretch in which Bob Devere kept them regularly booked, primarily at jazz clubs, with some college and university dates thrown into the mix. So the Dog, as it was affectionately known to the locals, was just another date in a string of dates. And yet this gig would have ramifications for Weather Report that lasted well beyond these three nights in Cleveland, as we shall see below.

Opened in October 1971, the Smiling Dog was housed in an old bowling alley. Bowling was big in the Midwest, so it was unusual for an alley to fail to draw enough business to sustain itself, but this one did. Perhaps this is because it was located in a rather seedy part of town off Interstate 71. As local saxophonist Ernie Krivda remembered, “If you were going to open up a club and bring in jazz, the last place you would think of was this particular area of West 25th Street. It was rough.”

There was a motorcycle shop across the street where bikers hung out working on their motorcycles. The Dog’s owner, Roger Bohn, looked the part, attired in biker leathers and a bowler hat, with his hair pulled back in a long ponytail. But his looks belied a big heart, and many young musicians grew to love hanging out there.

Bohn ripped out the bowling lanes and replaced them with a stage and tables and chairs. In front, there was a bar and a game area with shuffleboard and air hockey games—holdovers from the bowling alley days. A biker-type known as Bear ran the front of the house, looking out for the young ladies who worked as barmaids because, as drummer Skip Hadden put it, “you never knew what was going to happen with that crowd.” Hadden also remembers being pressed into server as a bouncer when he wasn’t working in the house band; it was that type of place.

At first the Dog relied on local musicians and folk artists. Eventually, Bohn got the idea of booking touring jazz acts. At the time, there wasn’t a jazz venue in Cleveland, so there wasn’t any competition. Plus, a club in Cleveland would offer an additional way station for touring bands traveling between the East Coast and the Midwest, making it an attractive proposition to them. The first major jazz band Bohn booked was Weather Report. “I feel Weather Report is the heaviest jazz to happen in Cleveland in a long time,” Bohn told a local newspaper.

If he was going to be successful in his bid to draw national jazz acts, he needed to make a good impression with this show. Realizing he didn’t have the type of sound reinforcement Weather Report required, Bohn asked a couple of young musicians to help him out: Alan Howarth and Brian Risner. They were fixtures in the local rock scene and sometimes performed at the Dog. Howarth and Risner brought their own equipment down to the club and provided Weather Report with proper sound.

In fact, it was better sound than Weather Report was accustomed to. Howarth and Risner had an early form of Quad sound, for instance. They impressed the band so much that Bob Devere wanted to hire them as the band’s road crew. At age 24, Howarth was the older of the two, so he was probably given first consideration, but he wasn’t prepared to hit the road. Risner was, so Devere hired him as the band’s first roadie. He was 19 years old. At the end of the Smiling Dog engagement, he kept Weather Report’s equipment in his parents’ garage before driving it to the next gig.

Almost immediately, Risner assumed a much larger role with the band than that of roadie. In addition to setting up the band’s gear before gigs and packed it up afterward, he also handled travel logistics, getting the equipment on and off airplanes and arranging ground transportation. “Basically, I did everything,” Risner recalled. “They would book the hotels, but as far as getting the band around and getting them set up, and doing their sound, and keeping all the electronics going, I was it.”

Risner was a capable electronics technician and sound mixer, and he quickly became Joe’s righthand man. Joe now had a technical accomplice willing and capable of pushing the envelope. In many ways, they were partners; Zawinul supplied the musical vision, and Risner provided the technical expertise to help him bring it to fruition. Risner kept the ARP 2600s operating (not an easy feat considering they weren’t designed for the rigors of the road), built a custom on-stage mixer for Joe’s keyboard rig, outfitted Zawinul’s Rhodes electric piano with a superior sound system, and attended to countless other tasks.

Ultimately Risner became Weather Report’s recording engineer, supervising the recording of 1982’s Weather Report album, and recording Procession, which was released in 1983. Brian was the longest-tenured member of the band after Joe and Wayne, and they christened him the “Chief Meteorologist” on the Heavy Weather album jacket.

Alan Howarth joined the band in 1977. By then Joe’s keyboard rig had expanded to the point that it required a fulltime technician. Like Risner, Howarth was well-versed in electronics and was well-suited to this task. He guided Joe through the acquisition of the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5 synthesizer, staying on for a couple of years before launching a career in motion picture sound design and music composition.

With the Weather Report gigs, the Smiling Dog became the jazz venue in Cleveland. Between 1972 and 1975, when the Dog closed, virtually every touring jazz band came through its doors, including Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, Stan Getz, Sun Ra, the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, McCoy Tyner, and Ornette Coleman.

Despite these names, the Dog perpetually operated on a shoestring budget. The club was always “hanging on by the skin of its teeth,” Bohn later acknowledged. Six months of unrelenting financial losses forced him to finally close the doors. “Good weeks were not enough to make up for bad weeks,” he said.

After Weather Report, Brian Risner toured with Miles Davis, among others, before settling in Los Angeles, where he specializes in sound design and sound editing for television and movie studios. When I mentioned to him that the fiftieth anniversary of his joining the band was upon us, he sent me this note:

Fifty years ago. You never know what door you’re going to walk through and what you’ll come out to on the other side. But once you do, there’s no turning back. There is no back, only forward. This was Joe and Wayne’s take on life and their music: moving forward—always moving forward.

I was twenty years younger than the masters. We explored new ideas and new music technologies. Joe was ready to be as big as The Who! From Sweetnighter thru Heavy Weather, and beyond to Procession, each album had different sonic textures and mixes.

Fifty years. Timeless music.

Forward.